Writer Fritz Dressler said: “Predicting the future is easy. It’s trying to figure out what’s going on now that’s hard.” This is especially true in a recession. In the past 150 years there have been 28 recessions, most of which were natural corrections to overblown booms. But recessions are uncertain and unpredictable. To rehash Tolstoy’s observation about happy and unhappy families, all booms resemble one another, but each recession is unique.

In 2008, the FTSE-100 moved up or down by more than 5% on 44 days: 22 of them in October. Volatility and uncertainty have soared.

So you may think I’m getting my excuses in early for predictions which will certainly miss the mark. But the main reason for thinking about the future is to have a chance of influencing it. Or preventing it. Or even building it.

I’m going to look at the future of UK retail over two timeframes – a medium term of 3 – 5 years, and a longer term of 10 – 15 years. Counter-intuitively the shorter timescale is more uncertain. Very long term predictions tend to come to pass sooner or later, just not necessarily as fast, or as slowly, as you think.

The retail scene in 2012

In 2012, the UK retail landscape will remain profoundly affected by the 2008/09 credit crunch. Consumers will still be suffering from squeezed discretionary income, and many are still working out negative housing equity. An era of frugality will have replaced the materialist excesses of the credit boom. Staying in has replaced the old going out: restaurant volumes are still stagnating. Durability and simplicity have overtaken disposability and fast fashion as the purchase trends.

The exceptional volume growth that fuelled many categories in the period 1998 – 2008 (such as clothing, homewares and electronics) is over. Retailers have fallen off the virtuous circle of deflating product prices, leading to increasing sales volumes and growing retailer profits. A weak UK currency, and the diminishing returns from overseas sourcing, have resulted in a margin squeeze and stagnating sales volumes.

By the end of this recession, we will have seen an acceleration in retailer consolidation. Recessions may be a slowdown in consumption, but they are a speed-up in industry change. In the 1990-92 recession, we saw the major DIY chains merge from 5 into 3, and Tesco seize the top grocer slot from Sainsbury’s. This time, we may see consolidation between retail sectors, with supermarkets buying up department stores and home retailers to extend their scale and capabilities in non-food.

The longer-term view

Retail can be an industry of fundamental change. Compared with, say, the media or technology sectors, there is a view that retail is relatively “mature”: that industry structure is stable. This is a view often subscribed to, explicitly or implicitly, by the management of retail companies. They come to believe that they work in a “mature” industry, and start to manage their businesses in a “mature” way, which means incrementally and with little imagination.

But a look back to the 1980s shows that the retail landscape does dramatically change over the longer term. And that imaginative competitors can therefore re-write the future.

In the 1980s, products were predominantly sourced from the UK. Central distribution was rare, with most suppliers delivering direct to store. The online channel had not been invented. Own brand penetration was only 15-20% and mostly an economy offer. There was no Sunday trading, stores were small and more numerous. The top four grocers held less than 30% of the market (compared to 75% today). And out-of-town did not exist.

So will the next era bring similarly profound changes?

What consumers will buy

By 2025, the UK population will be substantially wealthier – we can expect the effects of recession to be far behind us. But retail will fail to capture much of the growth in spending. A reliable guide to how consumers will spend in the future view is to look at top decile earners today: their spending patterns tend to blaze the trail for the average consumer of the future. On this basis it is likely that by 2025, only 20% of consumers’ total spend will go on retailing (the proportion is 32% today but has been steadily declining for decades). Income growth will instead be splashed on leisure, travel and housing. Of the household food budget, we can expect 50% to be spent on eating out (the number is 30% today, but is already at the 50% level in the US).

Very few retail categories will therefore see real growth. An exception will be health and beauty retailing as an ageing population is eager to look youthful and remain active.

Convenience, quality and ethics will become steadily more important as the top three criteria driving consumers’ choices. Convenience – especially speed and ease of purchase – will be critical to time-starved and impatient consumers: overwhelming range in huge but remote destination stores will be less of a draw. Exceptional performance will be the minimum standard of quality for the better informed and richer customers of the future. And ethical retailing will be the norm, with sustainability and fair trade permeating the mass market rather than a premium segment. Price will become less of a differentiator, as the ubiquity of price comparison software means consumers can now rely on price as a fair indicator of value.

How customers will shop

Perhaps the biggest change will be the way in which consumers shop. In 2008, we heard much about polarisation by price: consumers simultaneously trading up for luxury and trading down for bargains (the Prada and Primark effect). By 2025, this will have evolved into a polarisation by emotional engagement.

For products and missions where customers are disinterested in the purchase, automated reordering and home delivery will take care of everything. Consumers will be barely involved in the purchase of their milk, toilet rolls or other household commodities.

By contrast, where consumers see products as an expression of their individuality, they’ll expect indulgence and personalisation in an environment with superb advice and service. The shopping experience will be entertaining and sensual. Shoppers buying a new bed will expect to test it out in a sound-proofed, darkened room with a cup of cocoa, and then for every aspect from size, material and colour to be customised.

This polarisation will have a profound effect on retail channels. Regular, commodity purchases will increasingly be replenished through automated online order and home delivery. Meanwhile prime high streets and malls will become destination retail showrooms where customers can trial and engage with the product and service. Department stores will have to become thrilling, experienced-based destinations if they are to survive.

There will be a role for convenience retail close to home and work for frequent, top-up missions. But bulk physical retail in out-of-town locations will increasingly come under threat from direct channels. And secondary retail locations and small retail parades will empty and revert to residential use.

The future of online retailing

By 2025, the question “what proportion of shopping is done online” will cease to make sense. Connectivity will be continuous and ubiquitous and virtually all purchases will be in some way inspired or informed by online activity. At least half of all purchases will be ordered online and fulfilled directly. The impact of this will vary by category: for electronics and media, 80-90% of purchases will be ordered online for direct delivery: for other categories such as clothing, food or homewares, closer to 40%. But even for the balance, online research will be universal: while they stand in store, consumers’ personal devices will stream reviews, competing deals, and the recommendations of their social networks.

With the increasing demand for simplicity and convenience from consumers, a new service will emerge: online personal shopping advisers. These advisers are independent, impartial, and have a deep understanding of the lifestyles and preferences of their users.

In 2008, several start-ups emerged in this space (Crowdstorm, ThisNext, Kaboodle, Become, Stylehive), but companies like Google, Facebook or Twitter are also well placed to perform this role.

The role of the personal shopping adviser will vary by product and mission. For commodity purchases, the adviser will have delegated authority to transact and maintain household stocks of consumables. For emotionally engaged purchases, the adviser will recommend and inform. As a result, loyalty to individual retailers will substantially reduce.

Consumers’ real trusted brand will be their adviser and its knowledge of what their online social community buys and rates.

The demand for retail space

Overall demand for physical retail space will decline sharply. The increase in the online channel, only partly offset by overall growth in consumption, means at least 15% of retail space will retire. But there will be bigger changes in the mix of space: prime retail space and malls will remain valuable because consumers prefer them and because they are best suited to hosting the entertainment and experience which retail will need to provide. But secondary high streets and poor quality malls will dwindle and die (Figure 1).

Retail locations will become increasingly concentrated – by 2025 the top 70 UK retail destinations will capture 65% of footfall.

The rise of consumer awareness

Fairtrade and ethical sourcing movements are heralding a reawakening of consumers’ consciousness of the system that supplies them. Governments will also demand a blunter public health message to deal with the escalating costs of obesity and diabetes.

In response to these interests, most products will carry a chip or bar code which, when scanned with a mobile phone or personal device, will show the whole story and picture of that product and how it was produced. In the case of food for example, nutritional and dietary information, plus images of the farm, live video of the animals and carbon footprint.

The impact of production technology

By 2025, technological advances in basic food production will be profound. “Pharmafoods” will be mainstream, and factory-grown protein (pork in a petri dish) will have become commercialisable. Foods will promise anti-ageing or memory-boosting qualities, and will be tailored to individual genetic profiles or medical histories. Consequently the major global pharma, foods and genetics groups will have consolidated agri-business and control more of the food value chain. A similar trend to a more concentrated upstream supply base will apply in clothing and household products as a result of patented nanomaterials (such as stay-clean fabrics). Retailers’ ability to differentiate through simple recipe development or product design will have been correspondingly reduced.

But the global, automated food industry will develop alongside a local, artisanal one. Distrustful of food grown on an industrial scale, consumers will crave emotional compensation through natural and nostalgic foodstuffs. Concern over food security and carbon emissions will mean a return to regional and seasonal foods. Organic butchers and farmers’ markets will thrive.

Retailers’ role in the value chain

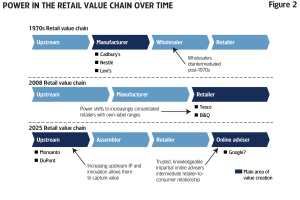

The long-term evolution of the value chain has generally been pretty favourable for retailers. As retailers concentrated and build their own brands, more and more of the “profit pie” in the value chain has ended up in their shareholders’ pockets. Wholesalers and producers have felt the squeeze.

But by 2025, this trend will no longer apply. As we have seen, two new players will start gaining power and value: the upstream technology owners (GM patent owners, nano-technology owners and so on), and the online adviser who could end up owning the interface with the consumer (Figure 2). In this world, retailers will struggle to maintain their traditional role of specifying and selecting product for their target customers. Online shopping advisers threaten to do for buying departments what Wikipedia did for Encyclopaedia Britannica.

Retailer profitability

By 2025, retailers may fondly remember the earlier part of the century as a uniquely benign age. Between 1996 – 2008, a virtuous circle operated of gently declining cost of goods, widening gross margins, modestly increasing operating costs and growing volumes (Figure 3).

By 2025, retailers may fondly remember the earlier part of the century as a uniquely benign age. Between 1996 – 2008, a virtuous circle operated of gently declining cost of goods, widening gross margins, modestly increasing operating costs and growing volumes (Figure 3).

From 2008 the virtuous circle was brutally yanked into reverse. Cost of goods started inflating: both because the gains of shifting supply to the Far East began to run out, and also because of the depreciation of the pound against the renminbi. Operational costs also inflated. As retail demand concentrated into prime locations, rent in these spaces increased. Energy and utility costs also increased. Reductions in staff labour costs due to technology (such as RFID automated check-outs) only partly offset these effects.

By 2025, retailers will also pay significant carbon taxes although, sensitive to this as well as to consumer pressures, retail will have surpassed other industries in reducing its environmental impact. Packaging will be minimised, home delivery will be zero-emission and supply chains will be highly efficient.

The importance of scale

Given all these trends, the importance of retailer scale will massively increase. To survive and thrive, retailers will need to bargain with strong suppliers, to adopt technology which reduces costs, and to invest in capturing customer information and personalising their services. For all these reasons and more, scale will count on a global, not just a national level (Figure 4). By 2025, there will be fewer, much larger retailers. And those retailers will have moved well beyond their home country to capture growth in the emerging BRIC markets.

Given all these trends, the importance of retailer scale will massively increase. To survive and thrive, retailers will need to bargain with strong suppliers, to adopt technology which reduces costs, and to invest in capturing customer information and personalising their services. For all these reasons and more, scale will count on a global, not just a national level (Figure 4). By 2025, there will be fewer, much larger retailers. And those retailers will have moved well beyond their home country to capture growth in the emerging BRIC markets.

Learning from the future

To return to the theme, the only purpose of thinking about the future is not to predict it, but to shape it. At the moment, weathering the storm is likely to be foremost of mind – lowering the breakeven and husbanding cash. But it is more important than ever to concentrate every resource on long term winning positions (the growth categories, channels, locations, and customers) and disinvest from the rest.

A downturn can also be a unique opportunity to transform your position. How will – or should – your sector be structured for the next cycle? How strong will the scale effects be, and will you be on the right end of these forces? Can you play in consolidation now, when asset prices are low, competitors may be weakened, or governments permit moves which are otherwise impossible?

The fog of recession is thick. But the future comes towards us even faster. This is the time for the general to be focused not just on the battle, but on the war.

This article first appeared in Market Leader, Quarter 2, 2009